Let Me Enfold Thee

An Essay on Basketball by Gonzaga Faculty Member Shann Ray Ferch

Let me enfold thee, and hold thee to my heart.

What is it like to be a college basketball player?

Probably quite a bit similar to what it’s like being a college student, or a dancer, a poet, or a scientist. College basketball involves a great dream. We might say the dream is life, and then we might wonder, what does life ask of us? The answer may mean the difference between despair and hope; or the distance, nuanced, oblique, between darkness and light; or the resolution and peace that come of being in the presence of beloved others who have loved us and changed us forever.

Gonzaga University has enjoyed a sustained and by some accounts miraculous journey into the heart of college basketball. For those who love basketball and have been graced to witness the journey, there remains both the beauty and vigor of excellence developed over many days, months, and years, and also the ultimate dream of the sport: the possibility of a National Championship. At each level of competitive basketball every player who seeks a higher goal holds the dream of a championship very close. Whether or not the dream is realized is a matter left to the dynamic interplay of devotion, fortitude, chemistry, chance, fate, and luck.

This essay* is a mosaic of my own experiences playing basketball in high school, college, and in the German Bundesliga, and finding myself on the other side of the dream, held by even greater dreams about love, forgiveness, reconciliation, wholeness, and the mystery of the Divine.

* Parts of this essay appeared previously in Narrative Magazine and the book Blood Fire Vapor Smoke

In the dark I still line up the seams of the ball to the form of my fingers. I see the rim, the follow-through, the arm lifted and extended, a pure jump shot with a clean release and good form. I see the long-range trajectory and the ball on a slow backspin arcing toward the hoop, the net waiting for the swish.

In Montana, high school basketball is a thing as strong as family or work and when I grew up Jonathan Takes Enemy, a member of the Apsaalooké (Crow) Nation, was the best basketball player in the state. He led Hardin High, a school with years of losing tradition, into the state spotlight, carrying the team and the community on his shoulders all the way to the state tournament where he averaged 41 points per game. He created legendary moments that decades later are still mentioned in state basketball circles, and he did so with a force that made me both fear and respect him. On the court, nothing was outside the realm of his skill: the jump shot, the drive, the sweeping left-handed finger roll, the deep fade-away jumper. He could deliver what we all dreamed of, and with a venom that said don’t get in my way.

I was a year younger than Jonathan, playing for an all-white school in Livingston when our teams met in the divisional tournament and he and the Hardin Bulldogs delivered us a crushing 17-point defeat. At the close of the third quarter with the clock winding down and his team with a comfortable lead, Takes Enemy pulled up from one step in front of half-court and shot a straight, clean jumper. Though the range of it was more than 20 feet beyond the three-point line, his form remained pure. The audacity and raw beauty of the shot hushed the crowd. A common knowledge came to everyone: few people can even throw a basketball that far with any accuracy, let alone take a real shot with good form. Takes Enemy landed and as the ball was in the air he turned, no longer watching the flight of the ball, and began to walk back toward his team bench. The buzzer sounded, he put his fist high, the shot swished into the net. The crowd erupted.

Many of these young men did not escape the violence that surrounded the alcohol and drug traffic on the reservations, but their natural flow on the court inspired me toward the kind of boldness that gives artistry and freedom to any endeavor. Such boldness is akin to passion. For these young men, and for myself at that time, our passion was basketball.

But rather than creating in me my own intrepid response, seeing Takes Enemy only emphasized how little I knew of courage, not just on the basketball court, but in life. Takes Enemy breathed a confidence I lacked, a leadership potential that lived and moved. Robert Greenleaf said, “A mark of leaders, an attribute that puts them in a position to show the way for others, is that they are better than most at pointing the direction.” Takes Enemy was better than most. He and his team worked as one as they played with fluidity and abandon. I began to look for this way of life as an athlete and as a person. The search brought me to people who lived life not through dominance or coercion but through love and freedom of movement.

In the half dark of the house, a light burning over my shoulder, I find myself asking who commandeers the vessels of our dreams? I see Jonathan Takes Enemy like a war horse running, fierce and filled with immense power. The question gives me pause to remember him and his artistry, and how he played for something more.

By the time my brother Kral and I reached high school, we both had the dream, Kral already on his way to the top, me two years younger and trying to learn everything I could. We’d received the dream equally from our father and from the rez, the Crow rez at Plenty Coups, and the Tsitsistas (Northern Cheyenne) rez in the southeast corner of Montana. In Montana tribal basketball is a game of speed and precision passing, a form of controlled wildness that is hard to come by in non-reservation basketball circles. Fast and quick-handed, the rez ballers rise like something elemental, finding each other with sleight of hand stylings and no-look passes, pressing and cutting in stream-like movements that converge to rivers, taking down passing lanes with no will but to create chaos and action and fury, the kind of kindle that smolders and leaps up to set whole forests aflame.

Kral and I lost the dream late, both having made it to the D-1 level, both with opportunity to play overseas, but neither of us making the NBA.

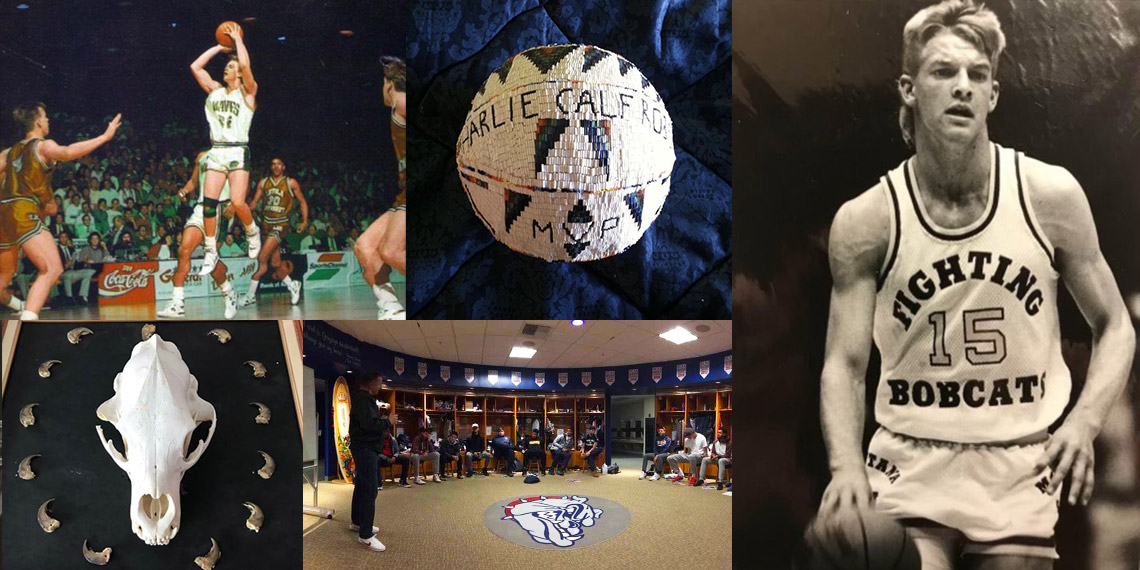

Along the way, I helped fulfill our father’s tenacious hopes: two state championships at Park High in Livingston, one first as a sophomore with Kral, a massive win in which the final score was 104 to 64, with Kral totaling 46 points, 20 rebounds, and three dunks. And one two years later when I was a senior with a band of runners that averaged nearly 90 points a game before there was a three-point line. We took the title in what sportswriters still refer to as the greatest game in Montana high school basketball history, a 99-97 double-overtime thriller in 85’ at the Max Worthington Arena at Montana State University, before a crowd of 10,000.

Afterward on the bus ride through the mountains I remember my chest pressed to the back of the seat as I stared behind us. The post-game show blared over the speakers, everyone still whooping and hollering. “We’re comin’ home!” the radio man yelled, “We’re coming home!” and from the wide back window I saw a line of cars miles long and lit up, snaking from the flat before Livingston all the way up the pass to Bozeman. The dream of a dream, the Niitsítapi and the Apsaalooké, the Blackfeet and the Crow, the Nēhilawē and the Tsitsistas, the Cree and the Northern Cheyenne, the white boys, the enemies and the friends, and the clean line of basketball walking us out toward skeletal hoops in the dead of winter, the hollow in our eyes lonely but lovely in its way.

At Montana State University, I played shooting guard on the last team in the league my freshman year. Our team: seven Black men from all across America and five White kids mostly from Montana. We had a marvelous, magical point guard from Portland named Tony Hampton. He was lightning fast with wonderful ball-handling skills and exceptional court vision. He brought us together with seven games left in the season. Our record at the time was 7 wins, 16 losses. Last place in the conference. “We are getting shoved down by this coaching staff,” he said, and I remember how the criticism and malice were thick from the coaches. Their jobs were on the line. They’d lost touch with their players. Their players had lost touch with them. Tony said, “We need to band together right now. No one is going to do it for us. Whenever you see a teammate dogged by a coach, go up and give that teammate love. Tell him good job. Keep it up. We’re in this together.”

A team talk like that doesn’t typically change a season.

This one did.

Tony spoke the words. We followed him and did what he asked, and we went on a seven-game win streak, starting that very night when we beat the 17th-ranked team in the country, on the road. The streak didn’t end until the NCAA tournament eight games later. In that stretch, Tony averaged 19 points and 11 assists per game. He led the way and we were unfazed by outside degradation. We had our own inner strength. Playing as one, we won the final three games of the regular season. We entered the Big Sky Conference tournament in last place and beat the fourth-, second-, and first-place teams in the league to advance to March Madness. When we came home from the conference tournament as champions, it felt like the entire town of Bozeman was at the airport to greet us. We waded through a river of people giving high fives and held a fiery pep rally with speeches and roars of applause.

We went on to the NCAA tournament as the last-ranked team, the 64th team in a tournament which at that time had only 64 teams. We were slated to play St. John’s, the number one team in the nation. We faced off in the first game of the southwest regional at Long Beach, and far into the second half we were up by four. St. John’s featured future NBA players Mark Jackson (future NBA All-Star), Walter Berry (collegiate player of the year), and Shelton Jones (future winner of the NBA dunk contest). We featured no one with national recognition. We played well and had the lead late in the second half, but in the end we lost by nine.

When my brother graduated from Montana State I transferred and played my final two seasons of college basketball for Pepperdine University. At that time, Pepperdine had been a league-leading team for many years. Our main rival was Loyola Marymount University, featuring consensus All-American Hank Gathers and the multi-talented scorer Bo Kimble. My senior year at Pepperdine we beat Loyola Marymount 127-114 in a true barn-burner! Also a fine grudge match, considering they beat us earlier in the season at their place. We were set to play each other in the championship game of the West Coast Conference tournament but before we could meet at the top of the bracket, Hank died, and the tournament was immediately canceled.

The funeral was in Los Angeles, a ceremony of gut-wrenching grief and bereavement in which we gathered to honor one of the nation’s young most-radiant men. We prayed for him and for his family and for all who would come after him bearing his legacy of love for the game, elite athleticism, and the gift of living life to the full. His team went on to the NCAA tournament and made it all the way to the Elite 8. Bo Kimble shot his first free-throw of the NCAA tournament left-handed in honor of Hank. The shot went in. The nation mourned. The athletes who knew Hank were never the same.

As a freshman in high school, I was tiny, barely five feet tall, and my goal was to play Division 1 basketball. I’d had this goal since I was a child and because of my height and weight it seemed impossible, and actually felt impossible. I was small, but I made a deal with myself to do whatever it might take from my end to try to get to the D-1 level, so if I did not accomplish the goal, I knew at least I had given my all. I grew eight inches the summer before my sophomore year in high school, thanked heaven, and began to think perhaps the goal was not totally out of reach.

Hour after hour. Everyday. The dream was now fully formed, bright shining, and excruciating. I played 8 hours per day before my junior year, 10 hours per day before my senior season. At the height of it I played 17 hours in one day. Hours of solitude and physical exhaustion were plentiful. I gave my life to the discipline of being a point guard and a shooting guard. I worked on moves, passing, shooting, defending, ball handling. The regimen involved getting up at 7 a.m. at the singlewide trailer we lived in, on my bike by 7:40, traveling the highway toward Livingston, yellow transistor radio (borrowed from my mom) in the front pocket of my windbreaker, the ball tucked up under the coat, and me riding to Eastside, the court bordered by a grade school to the east, the sheriff’s station and the firehall to the north, and small houses to the west. A few blocks south, the Yellowstone River moved and churned and flowed east. Above the river a wall of mountains reached halfway up the sky.

Mostly I was by myself, but because the town had a love for basketball, there were many hours with friends too. In those moments with others, or isolated hours trying to hone my individual basketball skills, I faced many, many frustrations, but finally the body broke into the delight of hard work and found a rhythm, a pattern in which there was the slow advance toward something greater than oneself. Often the threshold of life is a descent into darkness, a powerful and intimate and abiding darkness in which the light finally emerges.

“Beauty will save the world,” Dostoevsky said.

Because of basketball I know there exists the reality of being encumbered or full of grace, beset with darkness and or in convergence with light. This interplay echoes the wholly realized vision of exceptional point guards and the daring of pure shooting guards, met with fortitude even under immense pressure.

At Eastside, both low end and high end have square metal backboards marked by quarter-sized holes to keep the wind from knocking the baskets down. Livingston is the fifth windiest city in the world. The playground has a slant to it that makes one basket lower than the other. The low end is nine-feet, 10 inches high, and we all come here to throw down in the summer. Too small, they say, but we don’t listen. Inside-outside, between-the-legs, behind-the-back, cross it up, skip-to-my-lou, fake and go, doesn't matter, any of these lose the defender. Then we rise up and throw down. We rig up a break-away on the rim and because of the way we hang on it in the summer, our hands get thick and tough. We can all dunk now, so the break-away is a necessity, a spring-loaded rim made to handle the power of power-dunks. The break-away rim came into being after Darryl Dawkins, nicknamed Chocolate Thunder, broke two of the big glass backboards in the NBA. On the first one Dawkins’ force was so immense the glass caved in and fell out the back of the frame. On the second, the window exploded and everyone ducked their heads and ran to avoid the fractured glass that flew from one end of the court to the other. Within two years every high school in the nation had break-aways, and my friends and I convinced our assistant coach to give us one so we could put it up on the low end at Eastside.

The high end is the shooter's end, made for the pure shooter, a silver ring 10-feet, two inches high with a long white net. At night the car lights bring it alive, rim and backboard like an industrial artwork, everything mounted on a steel-grey pole that stems down into the concrete, down deep into the hard soil.

A senior in high school, I’m 17. I leave the car lights on, cut the engine and grab my basketball from the heat in the passenger foot space. I step out. The air is crisp. The wind carries the cold, dry smell of autumn, and further down, more faint, the smell of roots, the smell of earth. Out over the city, strands of cloud turn grey, then black. When the sun goes down there is a depth of night unfathomable, the darkness rent by a flurry of stars.

I call the ballers by name, the great Native basketball legends, some my own contemporaries, some who came before. I learn from them and receive the river, their smoothness, their brazenness, like the Yellowstone River seven blocks south, dark and wide, stronger than the city it surrounds, perfect in form where it moves and speaks, bound by night. If I listen my heroes lift me out away from here, fly me farther than they flew themselves. In Montana, young men are Native and they are White, loving, hating. At Lodge Grass, at Lame Deer, I was afraid at first. But now I see. The speaking and the listening, the welcoming: Tim Falls Down, Marty Round Face and Max and Luke Spotted Bear from Plenty Coups; Joe Pretty Paint from Lodge Grass; and at St. Labre, Juneau Plenty Hawk, Willie Gardner, and Fred and Paul Deputee. All I loved, all I watched with wonder—and few got free.

Most played ball for my father, a few for rival teams. Some I watched as a child, and I loved the uncontrolled nature of their moves. Some I grew up playing against. And some I merely heard of in basketball circles years later, the rumble of their greatness, the stories of games won or lost on last second shots.

The body in unison, the step, the gather, the arc of the ball in the air like a crescent moon—the follow-through a small well-lit cathedral, the correct push and the floppy wrist, the proper backspin, the arm held high, the night, the ball, the basket, everything illumined.

We are given moments like these, to rise with Highwalker and Falls Down and Spotted Bear, with Round Face and Old Bull and Takes Enemy: to shoot the jump shot and feel the follow through that lifts and finds a path in the air, the sound, the sweetness of the ball on a solitary arc in darkness as the ball falls into the net.

All is complete. The maze lies open, an imprint that reminds me of the Highline, the Blackfeet and Charlie Calf Robe, the Crow and Joe Pretty Paint, the Cheyenne and Highwalker, a form of forms that is a memory trace and the weaving of a line begun by Native men, by White men, by my father and Calf Robe’s and Pretty Paint’s and Highwalker’s fathers, by our fathers’ fathers, and by all the fathers that have gone before, some of them distant and many gone, all of them beautiful in their way.

Fresh from professional ball in Germany I went with my dad to the Charlie Calf Robe Memorial Tournament on the Blackfeet rez in northeast Montana. The tribe devoted an entire halftime to my father and he didn't even coach on that reservation. They presented him with a beaded belt buckle and a blanket for the coaching he’d done on other reservations, the Cheynne rez, the Crow rez—to show their respect for him as an elder who was a friend to the Native Nations of Montana. During the ceremony they wrapped the blanket around his shoulders, signifying he would always be welcome in the tribe.

On that weekend with him, I received an unforeseen wholly unique gift. Dedicated as a memorial to the high school athlete Charlie Calf Robe, a young Blackfeet artist, long distance runner, and basketball player who died young, the tournament was a form of community grieving over the loss of a beloved son. The Most Valuable Player award was made by Charlie’s wife, Honey Davis, who spent nine months crafting an entirely beaded basketball for the event. When the tribe and Honey herself presented the ball to me, and I walked through the gym with my father, an old Blackfeet man approached us. He touched my arm, and smiled a wide smile.

“You can’t dribble that one, sonny” he said.

I saw my father’s father only a handful of times.

He lived in little more than a one room shack in Circle, Montana. In the shack next door was my grandfather’s brother, a trapper who dried animal hides on boards and leaned them against walls and tables. I remember rattlesnake rattles in a small pile on the surface of a wooden three-legged stool. A hunting knife with a horn handle. On the floor, small and medium-sized closed steel traps. An old rifle in the corner near the door.

My father and I drive the two-lane highway as we enter town. We pick up my grandfather stumbling drunk down the middle of the road and take him home.

Years later my grandpa sits in the same worn linoleum kitchen in an old metal chair with vinyl backing. Dim light from the window. His legs crossed, a rolled cigarette lit in his left hand, he runs his right hand through a shock of silver hair atop his head, bangs yellowed by nicotine. Bent or upright or sideways, empty beer cans litter the floor.

“Who is it?” he says, squinting into the dark.

“Tommy,” my dad says, “your son.”

“Who?” the old man says.

When we leave, my grandpa still doesn’t recognize him.

On the way home through the dark, I watch my father’s eyes.

My grandfather was largely isolated late in life. No family members were near him when he died. He once loved to walk the hills after the spring runoff in search of arrowheads with his family. But in my grandpa’s condition before death his desire for life was eclipsed. He became morose and very depressed. In the end, alcohol killed him.

There’s J.P. Batista, a powerful player dubbed “The Beast” when he played here because he could score on anyone, and if he was hungry on the court, which was always, we said “Feed the Beast!” There’s David Pendergraft, perhaps the most beloved generational talent in Gonzaga’s history because he played with unquenchable fire and if he was guarding the best player on the other team, which was nearly always, the other team was in trouble. There’s Ronny Turiaf, a man whose heart was as big as the world, on and off the court. Finally, there’s Mike Nilson, the soul of the first GU teams to break through into the dream of advancing far into March Madness, a beautiful person with uncommon tenacity and loyalty, who serves others with grace and ease. Too many to be named, the players the community has welcomed, known and loved leave a legacy we as dear as any championship run.

In present-day Montana, with its cold winters and far distant towns, the love of high school basketball is a time-honored tradition. Native teams have most often dominated the basketball landscape, winning multiple state titles on the shoulders of modern day warriors who are both highly skilled and intrepid.

Tribal basketball comes like a fresh wind to change the climate of the reservation from downtrodden to celebrational. Plenty Coups with Luke Spotted Bear and Dana Goes Ahead won two state championships in the early eighties. After that, Lodge Grass, under Elvis Old Bull won three straight. Jonathan Takes Enemy remains perhaps the most revered. Deep finger rolls with either hand, his jumpshot a thing of beauty, with his quick vertical leap he threw down 360s, and with power. We played against each other numerous times in high school, his teams still revered by the old guard, a competition fiery and glorious, and then we went our separate ways.

For a few months he attended Sheridan Community College in Wyoming then dropped out.

He played city league, his name appearing in the Billings papers with him scoring over 60 points on occasion, and once 73.

Later I heard he’d done some drinking, gained weight, and become mostly immobile.

But soon after that he cleaned up, lost weight, earned a scholarship at Rocky Mountain College and formed a nice career averaging a bundle of assists and over 20 points a game. A prize-winning article on Takes Enemy appeared in “Sports Illustrated.”

A few years ago we sat down again at a tournament called the Big Sky Games. We didn’t talk much about the past. He’d been off the Crow reservation for awhile, living on the Yakima reservation in Washington. He said he felt he had to leave Montana. He’d found a good job. His vision was on his family. The way his eyes lit up when he spoke of his daughter was a clear reflection of his life, a man willing to sacrifice to enrich others. His face was full of promise, and thinking of her he smiled. “She’ll graduate from high school this year,” he said, and it became apparent to me that the happiness he felt was greater than all the fame that came of the personal honors he had attained.

Jonathan Takes Enemy navigated the personal terrain necessary to be present to to his daughter. I hope to follow him and be present for my daughters. By walking into and through the night he eventually left the dark behind and found light rising to greet him.

Inside me still are the memories of players I knew as a boy, the stories of basketball legends. From Montana, from Gonzaga, from Europe. The geography of such stories still shapes the way I speak or grow quiet, and shapes my understanding of things that begin in fine lines and continue until all the lines are gathered and woven to a greater image. That image, circular, airborne, is the outline and the body of my hope.

The drive is not far and before long I’m at Mission Park. I take the ball from the space in the backseat of my car and walk out onto the court. I approach the top of the key where I bounce the ball twice before I gather and release a high-arcing jumpshot.

Beside me, Blake Walks Nice sends his jumper into the air and Joe Pretty Paint’s follow through stands like the neck of a swan.

The ball falls from the sky toward the open rim and the diamond-patterned net.

Behind us and to the side only darkness.

An arm of steel extends from the high corner of a nearby building.

A light burns there.

As we draw near to another NCAA tournament, I don’t want to forget the dream. The following poem is written in honor of Jose Hernandez, Tony Hampton, Melichi Four Bear, Gernell Killsnight, Jonathan Takes Enemy, Dexter Howard, Doug Christie, J.P. Batista, Ronny Turiaf, David Pendergraft, Mike Nilson, Tim Falls Down, Bobby Jones, Paul Deputee, Blake Walks Nice, Ron Moses and so many other men, each of us inscribed by culture, intuition, race, and love, each of us united by an elegant game, and united by giving ourselves so that others might become more beautiful, more holy. Of the group above, one died a difficult death after years in prison at the outskirts of San Francisco, another was shot in the head by a high-powered rifle at a party near Crow Agency, a third was knifed to death outside Jim Town Bar, a fourth took his own life by hanging, a fifth died of an alcohol-laced car wreck when his vehicle flew from a bridge into a winter river. The rest are still alive. The rest still love with an undying love those who have passed before us to the next world. We receive from them the blessing they give, and we ask God for the mercy to keep the dream.

GODFIRE

the way your hands moved

through mid-air reaching

for round light

leather has always been

to me not unlike

the intimate fusion

that connects the core

of high magnitude stars

in the place where

God shapes bones

and ligament, fingers,

thumb and palm

we hated each other, brother,

until basketball made me

a point guard and

you a swing man flyer

who walked on wind

collectively we’d set our bodies

to beat one another until

our faces cracked like porcelain

and blood-rivers ran the

cheek-bone shelves

of a south sunk in wine-water

because America meant

us for violence

but better than we knew

God knew us

and now that the game is over

i can’t unremember you

enfolding me as I hold you

to my heart and you cup your hand

to the back of my head

About the Author

Poet and prose writer Shann Ray Ferch teaches leadership and forgiveness studies at Gonzaga University. Ferch is the author of a work of leadership and political theory, Forgiveness and Power in the Age of Atrocity: Servant Leadership as a Way of Life (Rowman & Littlefield), and co-editor of Servant-Leadership, Feminism, and Gender Well-Being (SUNY Press), Servant-Leadership and Forgiveness (SUNY Press), Global Servant-Leadership (Rowman &Littlefield), Conversations on Servant Leadership (SUNY Press) and The Spirit of Servant Leadership (Paulist Press). In his role as professor of leadership studies with the internationally renowned PhD program in Leadership Studies at Gonzaga, he has served as a visiting scholar in Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Americas. His novel, American Copper (Unbridled Press), is a love song to America revealing the radiant and profound life of Evelynne Lowry, a woman who transcends the national myth of regeneration through violence. The novel won the Foreword Book of the Year Readers’ Choice Award and the Western Writers of America Spur Award, and was a finalist for the Washington State Book Award, the High Plains Book Award and the Foreword Book of the Year Award for Literary Fiction. Explore more of his writing here.

- School of Leadership Studies

- Doctor of Philosophy in Leadership Studies